Science Chats Part 2 & 3: Ahklavik & Anguniaglaniq

Posted on Sept. 28, 2020

The Yukon North Slope is an incredible place to do research, attracting scientists from around the world. And, while research findings are often published in academic journals for other scientists, what comes out of these projects is important for community members, wildlife managers, and others. It is in everyone’s interest to communicate the science that is happening, and the values and interests of the Inuvialuit of the region.

We want to share some of this incredible work with you! Join us in these Science Chats, and check out the short interview between Michelle Gruben of the Aklavik Hunters and Trappers Committee, and Kayla Nanmak Arey, an Inuvialuit from Aklavik, as well as the interview between Kayla and Elizabeth Worden of the University of Manitoba, as they talk about the beluga whale harvest and what it means for community members.

Our second Science Chat is titled Ahklavik, which means ‘home of the barrenland grizzly’ in Inuvialuktun. The third is titled Anguniaglaniq and that means ‘hunting traditions.’ While we interviewed Michelle and Elizabeth separately, their stories are told together here, as they are very much intertwined.

Shingle Point (Tapqaq), a traditional hunting community on the Yukon North Slope ©Elizabeth Worden

Laying the Foundation for Great Research

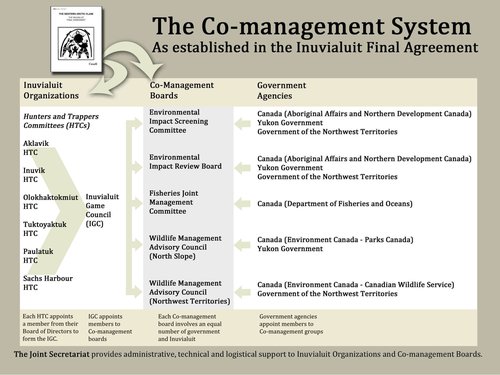

The Inuvialuit Final Agreement provides a framework for working in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, which includes the Yukon North Slope. Part of that framework are the community-based Hunters and Trappers Committees, an Inuvialuit organization that represents harvesters’ views in each community. Members are also knowledge holders when it comes to the land and wildlife.

Michelle Gruben is the Resource Person for the Aklavik Hunters and Trappers Committee (HTC). Each Inuvialuit community’s HTC appoints members from their Board of Directors to the Inuvialuit Game Council (IGC) who then appoints members to co-management groups such as WMAC NS. These co-management groups each have an equal number of Inuvialuit and government representatives.

‘We all co-manage together for the future, so our younger generation can be just as plentiful and healthy as us, as our ancestors were back then’ -Michelle Gruben

‘We all co-manage together for the future, so our younger generation can be just as plentiful and healthy as us, as our ancestors were back then’ -Michelle Gruben

In 2016, the first Beluga Summit was held in Inuvik. The beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas), Qilalugaq in Inuvialuit, is a medium-sized toothed whale. They reach maturity around seven years of age and can be 3.5 to 4.5 meters long. The population inhabiting the Northwest Territories Arctic Ocean is the Eastern Beaufort Sea population, a healthy and currently large population estimated at around 40,000 animals.

Harvest data from 1975 to 1995 showed an average annual harvest of 22 animals, and from 1996 to 2017 that number dropped to six. A notable change…

At this summit, the Aklavik Hunters and Trappers Committee proposed a project that would look at the beluga whale harvest, and hear people’s stories and perspectives of why the numbers of the Qilalugaq harvest were low for the community.

Collaborating for Success

By 2017 this project was underway. Michelle worked with Elizabeth Worden, a Research Associate from the University of Manitoba on the project. The end result was a research paper titled ‘Social-ecological changes and implications for understanding the declining beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas) harvest in Aklavik, NT.’ This paper was a collaboration with community members from Aklavik, and Elizabeth Worden and her supervisor Lisa Loseto.

The project explored the potential social and ecological reasons affecting the beluga whale harvest in Aklavik. Dorothy Ross and Clarence Kowana (both Aklavik residents) were research assistants for the project, and along with Elizabeth, they facilitated talks with community members about the past and present state of the beluga harvest. Soon after talking with people, they realized it also made sense to ask the community members what they thought for the future of the harvest. They heard that ecological changes such as erosion, and unpredictable and severe weather have been impacting the harvesting of belugas.

On the Beaufort Sea coastline ©Elizabeth Worden

Combined with the ecological changes, are social changes such as a loss of traditional knowledge and elders, as well as a modernizing community. It is not only one factor driving the reduced harvest of beluga whales in Aklavik. It is a complicated issue that requires community-based solutions, guided by Inuvialuit culture and needs.

An important part of community-driven research is allowing the space and time for sharing knowledge and experience – both of which are rooted in connection to the land (or sea in this case!). Elizabeth travelled to Shingle Point on the Yukon North Slope and experienced community life there. She was able to witness first-hand exactly what people were talking about in her interviews: ‘[It was] so good to situate a lot of what people were seeing, and stories, to real life.’ This connection and experience really grounded Elizabeth, and her research. She saw that the implications were real and direct. People’s livelihoods are impacted. The beluga whale harvest is more than just a traditional activity. We currently live on the food from these harvests of whales and other animals. This is a traditional activity that we still depend on, right now.

Michelle firmly believes that the beluga whale harvest, and traditional Inuvialuit lifestyle will continue to survive, and thrive in the future. And it is in part due to the cooperation of people and their projects, like the community and HTC of Aklavik, and researchers like Elizabeth coming together and meaningfully engaging with each other.

The collaborative results of this work are now available in the new paper "Social-ecological changes and implications for understanding the declining beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas) harvest in Aklavik, Northwest Territories." For more information, Michelle can be reached at the Aklavik Hunters and Trappers Committee and Elizabeth can be reached at her University of Manitoba office.

Our Science Chats series was created and developed by Kayla Nanmak Arey. She shares a little about herself below:

Nanmak is a name I share with my granny Jean Arey (my great grandmother). My nanak Nellie (grandmother), and my mom Carol say my granny was stubborn, and so was I. Inuvialuit names are passed down from generation to generation, and I am proud to have the name Nanmak. Translated, nanmak means to backpack. Specifically, for a working Inuit dog to carry things in, a nanmak.