Science Chats Part 5: Tariumi

Posted on Oct. 29, 2020

The Yukon North Slope is an incredible place to do research, attracting scientists from around the world. And, while research findings are often published in academic journals for other scientists, what comes out of these projects is important for community members, wildlife managers, and others. It is in everyone’s interest to communicate the science that is happening, and the values and interests of the Inuvialuit of the region.

We want to share some of this incredible work with you! Join us in these Science Chats and check out the short video between Cameron Eckert from Yukon Parks, and Kayla Nanmak Arey an Inuvialuit from Aklavik, as they talk Qikiqtaruk (Herschel Island) ecological monitoring!

Our fifth Science Chat is titled Tariumi. The letter r in Inuvialuktun makes a guttural or throaty sound, leading into the next letter sound. So tariumi is pronounced “da-*throaty sound-yu-me.” Da-*yu-me. This means “on the ocean” like where Qikiqtaruk lies, on the Arctic Ocean.

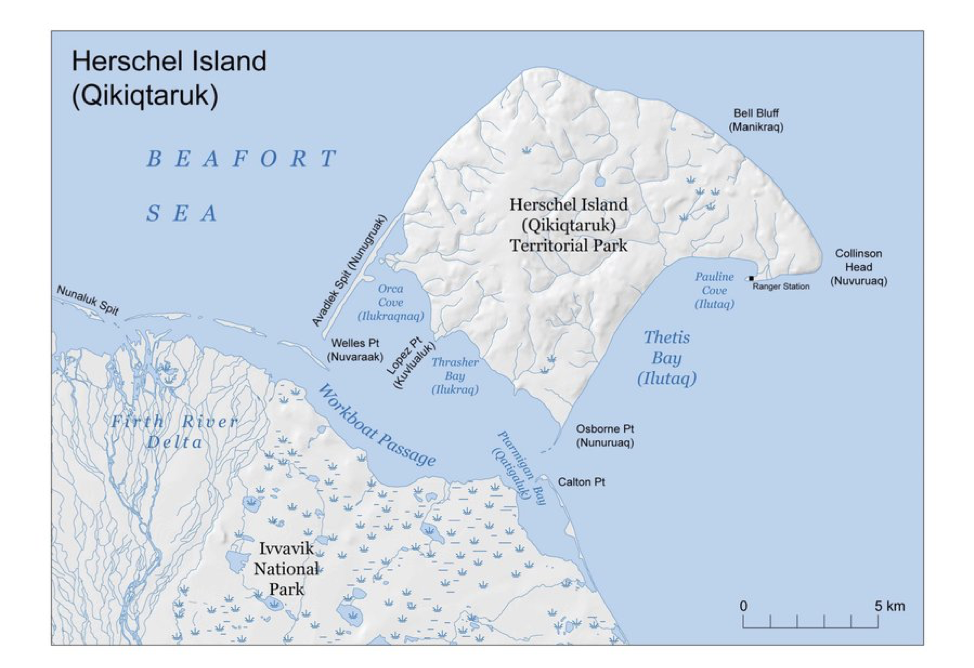

Qikiqtaruk, which is 116 km2 and lies five kilometers offshore of mainland Yukon North Slope ©WMAC NS

What Is Ecological Monitoring?

Ecological monitoring is making regular observations over time. Observations can be on plants and animals, as well as environmental conditions. The purpose is to better understand an environment’s past, present, and potentially future. The longer we observe something, the better we understand nuanced dynamics and capture environmental change.

As a conservation biologist with Yukon Parks, Cameron is responsible for coordinating the ecological monitoring programs for the territorial parks. The ecological monitoring program on Qikiqtaruk began in 1999. This program contributes to the vision statement of the park’s management plan, which states:

Those who manage and take care of the island work together to fulfill the Elders’ vision of Qikiqtaruk as a park to protect and sustain the ecological integrity and heritage values for generations to come.

These words inspire Cameron to ask: "Are the ecosystems functioning in a way they have in the past? Changing but continuing to function in a natural way?"

The program also works very closely with the Inuvialuit Park Rangers, who conduct much of the monitoring activities. The monitoring activities include observing the populations of birds and mammals, habitat changes and shifts in vegetation communities, coastal erosion, and permafrost. All these components offer information on the current – and potentially changing – state of the island.

Cameron looks out to sea at two female Common Eiders near Nuvuruaq (Collinson Head) ©Kayla Nanmak Arey

Why Is This Important?

Ecological monitoring is important here because Qikiqtaruk is a traditional gathering place and is still used regularly by Inuvialuit and Inupiaq travelling along the coast. It is important to understand the conditions that will impact travel plans or routes, as there are few places along the coast that are safe havens for travellers in small motorboats.

Spending time on the island with Inuvialuit is also a key aspect that Cameron focuses on for information sharing. Recently, the Youth and Elder’s Program started up, which sees Inuvialuit youth and Elders from Aklavik spend time at Qikiqtaruk together, practicing traditional activities, such as fishing and storytelling. This offers scientists and researchers who may be on the island the opportunity to interact with people from Aklavik, who have generations of knowledge about the island.

Getting up close and personal with the flora of Qikiqtaruk ©Cameron Eckert

Bringing In Youth

Cameron also worked on recruiting an Inuvialuit undergrad student to take part in the ecological monitoring program in 2018. This was how I became a part of the program; I got to bring my own knowledge of the lands and animals – much of which I owe to my nanak (grandmother). She always shared with me stories about her birthplace, Qikiqtaruk. I also got to apply my academic teachings.

During our island research, I helped Cameron survey birds, insects, whales, and plants. We also installed wildlife cameras to monitor the wildlife at specific locations. In the evenings I was lucky enough to fish. It was so special to cut and smoke my own fish again. I thought about how my family was also fishing not so far away at Shingle Point (Tapqaq). Having the opportunity to take part in scientific research happening on the North Slope, and also being able to practice my traditional activities has always been my goal.

Team Bird always on the lookout! In front of the community house (left), and along the beach (right) ©Kayla Nanmak Arey

Cameron and I called ourselves Team Bird, as we radio communicated with Team Shrub, also doing research on the island (stay tuned for an upcoming interview with Isla Meyers-Smith from Team Shrub)! Cameron has always been especially interested in birding, and I was eager to learn more about the behaviours and movement of bird species around us.

The following year another Inuvialuit undergrad, Jessica Norris, participated in the ecological monitoring program. This is such a great opportunity to foster connection to the land and provide valuable field experience for early career Inuvialuit scientists.

Jessica Norris (third from left) and Inuvialuit youth from the Elders and Youth Program, on Qikiqtaruk ©Cameron Eckert

What Can We Learn?

Inuvialuit have been observing the landscape closely since time immemorial. We understand the processes of the land and animals and know that changes are happening. But sometimes we need very specific data. Cameron talks about what the research and science bring. This includes the ability to quantify exactly which species are affected by climate change. Specific measurement and documentation of change supports our understanding of the rate of change for erosion for example, or the movement of new species onto Qikiqtaruk. With these data sets compiled over time we can better understand what is happening now, and importantly, what the implications are for subsistence activities and wildlife into the future. Coming back to the vision statement for the Qikiqtaruk management plan, the ecological integrity of the island is so important. As a result of decades of ecological monitoring, scientists and Inuvialuit alike are better positioned to respond to climate change.

Our Science Chats series was created and developed by Kayla Nanmak Arey. She shares a little about herself below:

Nanmak is a name I share with my granny Jean Arey (my great grandmother). My nanak Nellie (grandmother), and my mom Carol say my granny was stubborn, and so was I. Inuvialuit names are passed down from generation to generation, and I am proud to have the name Nanmak. Translated, nanmak means to backpack. Specifically, for a working Inuit dog to carry things in, a nanmak.