The Leading Edge of Polar Bear Research

Posted on July 27, 2020

In the western Arctic, Indigenous values and culture are encouraging scientists to explore new ways of gathering information on polar bears. This knowledge is critical.

The story of Inuvialuit (Inuit of the western Arctic) and nanuq (polar bear) has deep roots. Inuvialuit have harvested polar bears for generations and polar bears have been a top Arctic predator for thousands of years. It’s a profound relationship, bound together by sea ice, seals, and climate change.

Photo credit: (c) 2019 GNWT-ENR/Steven Baryluk.

With this deep connection comes a wealth of knowledge about the world of nanuq. As is tradition, this knowledge is passed from generation to generation. The Arctic environment is rapidly changing, though, and so too is this body of knowledge as both Inuvialuit and polar bears adapt to these changes.

Managing Together...

...Because Polar Bears Don’t See Borders.

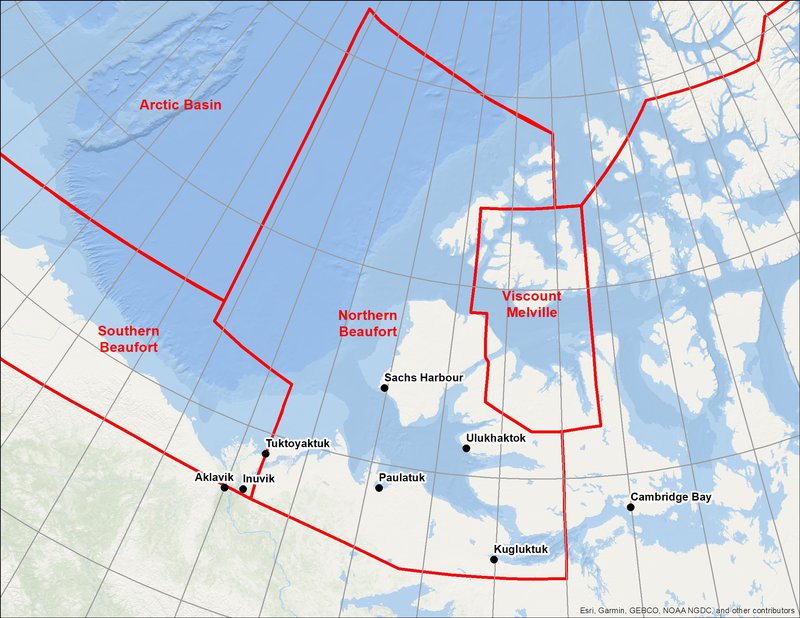

The Inuvialuit Final Agreement, signed in 1984, legally defined the role of the Inuvialuit in continuing to harvest and manage polar bears in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR). The Inuvialuit manage polar bears in the ISR collaboratively with the Yukon, NWT and Canada and partners from adjacent jurisdictions (Nunavut and the United States). The ISR is home to four polar bear subpopulations – the Southern Beaufort, Northern Beaufort, Viscount Melville and Arctic Basin. Three of these subpopulations are shared with neighbouring jurisdictions – Nunavut to the east and Alaska to the west. There are agreements in place that lay out shared management responsibility for these subpopulations.

Photo credit: John Lucas Jr., 2012.

The management goal for polar bears in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region is “To ensure the long-term persistence of healthy polar bears in the ISR while maintaining traditional Inuvialuit use” (Joint Secretariat, 2017). To maintain traditional use of polar bears, harvest quotas are set collaboratively through the co-management process, and allocated within the region by the Inuvialuit Game Council and local Hunters and Trappers Committees. In order to set a sustainable harvest level that supports the long-term persistence of healthy bears, management authorities need to have estimates of the population size (how many bears are within each management unit). This is tricky information to get though. Polar bears cover massive areas, most of which are incredibly remote – on an annual basis, female polar bears have been observed to travel anywhere from 940 to 5,095km (COSEWIC, 2018).

Map (above): Inuvialuit Settlement Region polar bear subpopulation boundaries, credit: (c) 2020 GNWT-ENR.

Developing Research Methods, Guided by Inuvialuit Values

Inuvialuit and management partners have been developing

culturally appropriate methods of obtaining population estimates for polar

bears. This means limiting disturbance of, and contact with, the bears as much

as possible. In the past, researchers sedated bears, took measurements and

fitted female bears with satellite collars. Although this provided valuable

information, the procedure is

not currently supported in the ISR. This was based on collars not releasing

(falling off) when they were supposed to, coupled with Inuvialuit concerns

about impacts to bears from the intrusiveness of the process and also

observations of collars rubbing on bears’ necks. In 2017, an aerial survey

method was used in the Southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation area – an approach that

has proven successful elsewhere, and is commonly used for surveying caribou.

This method didn’t work for in the ISR. In some of the other regions of Canada,

polar bears can be found concentrated along the coastal areas at certain times

of the year, but this isn’t the case in the ISR. Photo credit: John Lucas Jr., 2014.

Inuvialuit and management partners have been developing

culturally appropriate methods of obtaining population estimates for polar

bears. This means limiting disturbance of, and contact with, the bears as much

as possible. In the past, researchers sedated bears, took measurements and

fitted female bears with satellite collars. Although this provided valuable

information, the procedure is

not currently supported in the ISR. This was based on collars not releasing

(falling off) when they were supposed to, coupled with Inuvialuit concerns

about impacts to bears from the intrusiveness of the process and also

observations of collars rubbing on bears’ necks. In 2017, an aerial survey

method was used in the Southern Beaufort Sea subpopulation area – an approach that

has proven successful elsewhere, and is commonly used for surveying caribou.

This method didn’t work for in the ISR. In some of the other regions of Canada,

polar bears can be found concentrated along the coastal areas at certain times

of the year, but this isn’t the case in the ISR. Photo credit: John Lucas Jr., 2014.

Capturing Polar Bear DNA

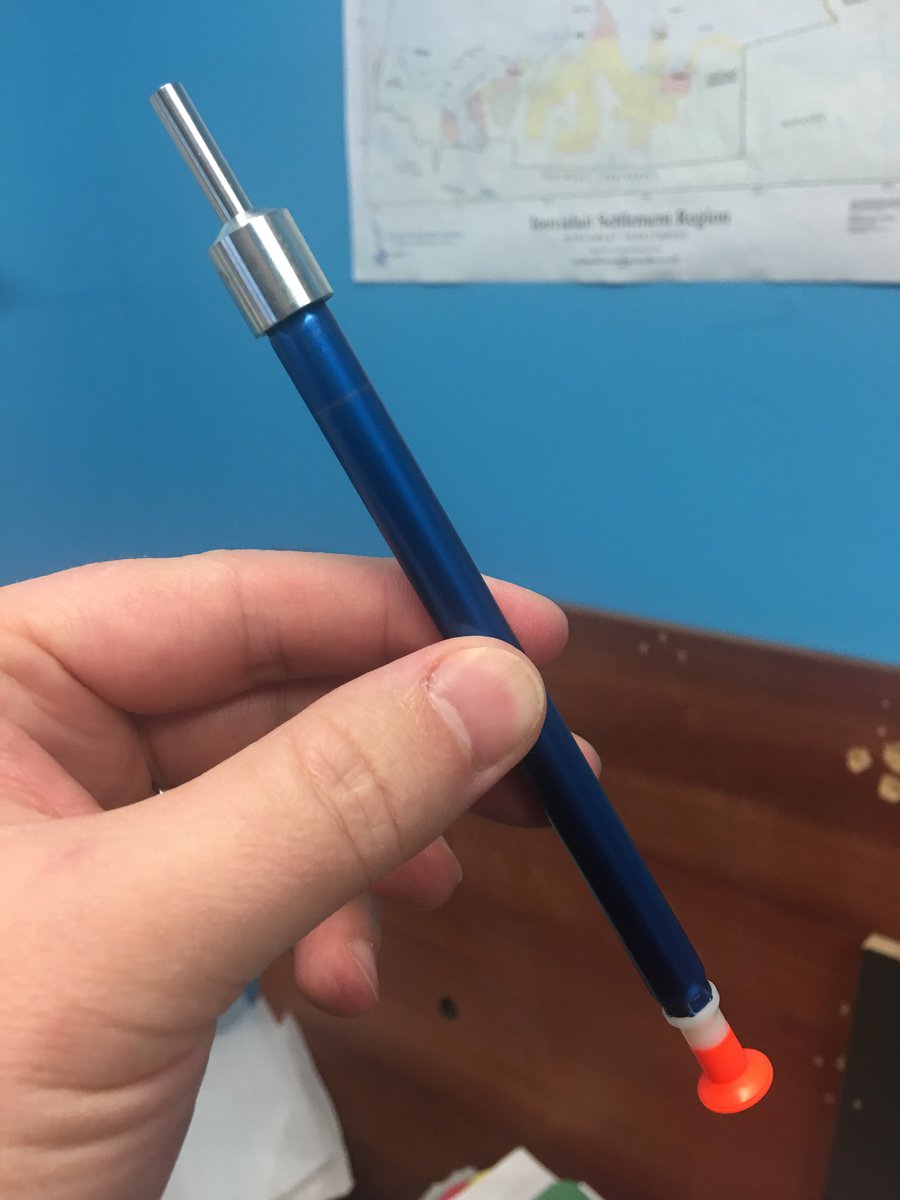

In 2019, researchers in the ISR started a new polar bear population survey, in partnership with neighbours in Alaska, and Nunavut. The method being used is called genetic mark-recapture, although there is no physical capturing of bears involved (think of it as mark-resample). Researchers fly in areas that cover a portion of polar bear habitat (while bears wander way out onto the sea ice, helicopters can only fly up to about 150 km from the shore, for safety reasons.) When researchers see a bear, they use a dart gun to dart it from a short distance (NOTE: only bears at least one year old or older are darted; cubs of the year are not sampled). The dart grabs a bit of skin and fur – about the size of a pea – from the bear and then falls out. The researchers wait for the bear to leave, then land their helicopter and retrieve the genetic sample from the sea ice. This results in genetic information from a sample of the subpopulation – which is now considered marked because the genetic information can identify individual bears.

Photo: a DNA biopsy dart. Credit: (c) 2018 GNWT-ENR/Steven Baryluk.

Researchers return and do the same flying and darting for three to four years total, collecting genetic information each year. As time goes on, some of those genetic samples will be from the same bear(s) – these are the ‘resampled’ bears. Statisticians can compare the portion of bears that are sampled once to those that are resampled to estimate the total abundance of bears in the study area. This population estimate comes with confidence intervals, which indicate the lower and higher range of how many bears may be in the population. We can’t get an exact number, but we can get pretty close if the surveys go well.

Photo: A DNA sample from a polar bear. Credit: (c) 2019 GNWT-ENR/Steven Baryluk.

What’s Next?

Because of COVID-19, the 2020 field season was cancelled. Researchers will aim to resume their genetic mark-recapture work in spring 2021. In the meantime, those involved in the survey (including WMAC (North Slope)) are thinking about how to incorporate Indigenous Knowledge and different forms of genetic material (e.g. hair snares, harvester samples) to help with producing population estimates.

By working together, we are refining and improving the information we have about polar bears. And we are moving towards science that is not just effective, but also culturally acceptable. Canadians, Alaskans, harvesters, scientists, and managers all have a role to play in the long-term persistence of healthy polar bears in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region.

Photo credit: John Lucas Jr., 2013.