Science Chats Part 7: Qayaqtuqłuni

Posted on Dec. 14, 2020

The Yukon North Slope is an incredible place to do research, attracting scientists from around the world. And, while research findings are often published in academic journals for other scientists, what comes out of these projects is important for community members, wildlife managers, and local businesses. It is in everyone’s interest to communicate the science that is happening, and the values and interests of the Inuvialuit of the region. We want to share some of this incredible work with you! Join us in these science chats and check out the short video on Facebook with Stephen Insley from the Wildlife Conservation Society, and Kayla Nanmak Arey, an Inuvialuk from Aklavik, as they discuss marine acoustics and the effects they have on marine wildlife.

This seventh chat is titled Qayaqtuqłuni, and this mean ‘using the kayak,’ like Inuvialuit would have traditionally done in the marine environment.

Field work, using a passive acoustic monitoring system (hydrophone) ©Stephen Insley

Research Beneath the Waves

Stephen Insley wants to see the big picture. And that takes time. Part of his work is long-term environmental monitoring, much like the monitoring that is done at Qikiqtaruk. To ensure this project is successful over many years, he partners with the Fisheries Joint Management Committee (FJMC), another co-management body for the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR), and the coastal ISR communities. Numerous years of data means he and his colleagues can start to see trends and relationships that may stay hidden with shorter research times.

Many of us in the north see and feel the effects of climate change already. For Stephen, these changes and their consequences drew him to this work – he wanted to contribute to an issue he thought he could have an impact on, and which would benefit the communities. Through this partnership, Stephen has been working in the ISR for about six years. The environmental monitoring work looks at how the marine plants and animals are affected, with a special focus on pinnipeds - the family that includes seals, sea lions, and walruses (Fun Fact: did you know walruses exhibit 'handedness,' preferring one flipper over the other just like humans!).

The seal monitoring program was implemented to keep a handle on what’s happening to the environment over time. For example, they look at where the seals live, how healthy they are, and what they are foraging. These types of information can be used as environmental indicators, a way to assess the overall health of the environment. Stephen also hopes to set up community-based ecological monitoring programs for the seal monitoring. This means working with, and building capacity in community members to take on the environmental monitoring themselves. This is also a great way for the communities to have input into the work, and talk about what is important, and how they are affected by these changing environments, as well. With this collaboration the work can be adapted to make the monitoring meaningful at the local level.

The seal monitoring program brings together many of the topics we have discussed in previous Science Chats: co-management, long-term ecological monitoring, meaningful engagement and collaboration, and climate change. Importantly, it is the science and community knowledge together that will help us adapt to a changing environment. One thing we haven’t talked about yet, but is definitely a part of that same environment, is the soundscape.

Data collection at sea ©Stephen Insley

Mapping Our Arctic Soundscapes

Marine animals communicate with sound. This, and the consequences of sound pollution in their environment, is something we humans might not often think about. The Beaufort Sea is home to beluga, ringed seals, bearded seals, and many species of fish; and all these animals make noise. It’s a real aquatic cacophony of life down there! For species like the beluga whale, sound is how they communicate, in the same way we greet our friends with a hello or raise our voice when there's danger. But, their environment is potentially about to become very noisy with cruise ship activity, and shipping routes opening up via the Northwest Passage (another product of climate change). How will acoustically-sensitive species, like beluga, manage in this changing soundscape?

This is where Stephen’s specialty comes in. Part of his educational background is in sound and acoustics, and how animals use sound. In chatting with Stephen, he explained how the Arctic Ocean is unique in that so far, it has been largely untouched by large scale human activity. If we think about the beluga again as an example, they are used to a very quiet environment, free of industrial noise. And they require this quiet environment for communication for finding mates, finding food, and living together. When a loud sound pollutes this soundscape, it masks the natural acoustic environment. It overpowers the animals' sounds, causing them to have to stay closer together, which affects their movement and range, or they just stop and try to escape the noise.

A closer look at a hydrophone ©Stephen Insley

So why is this important to know? Is sound pollution really that big of an issue? It definitely can be. Imagine that suddenly your house was at the very end of an airport with constant traffic. It would be extremely disruptive to your day-to-day life. Or imagine standing three feet from shooting firecrackers, this would be akin to what a whale would hear from single-pulse boom ‘sound pulses’ from underwater airguns used in oil exploration.

Stephen’s work looks at these marine acoustic environments. Using a passive acoustic monitoring system (hydrophone) that is lowered into the water, he can measure the biological and environmental sounds. With this information he can determine where shipping routes may be safer for the animals around, or where traffic can be directed further away from an area. It takes understanding how the natural soundscape sounds, and what animals are there and what they do, to understand what may be detrimental to their health.

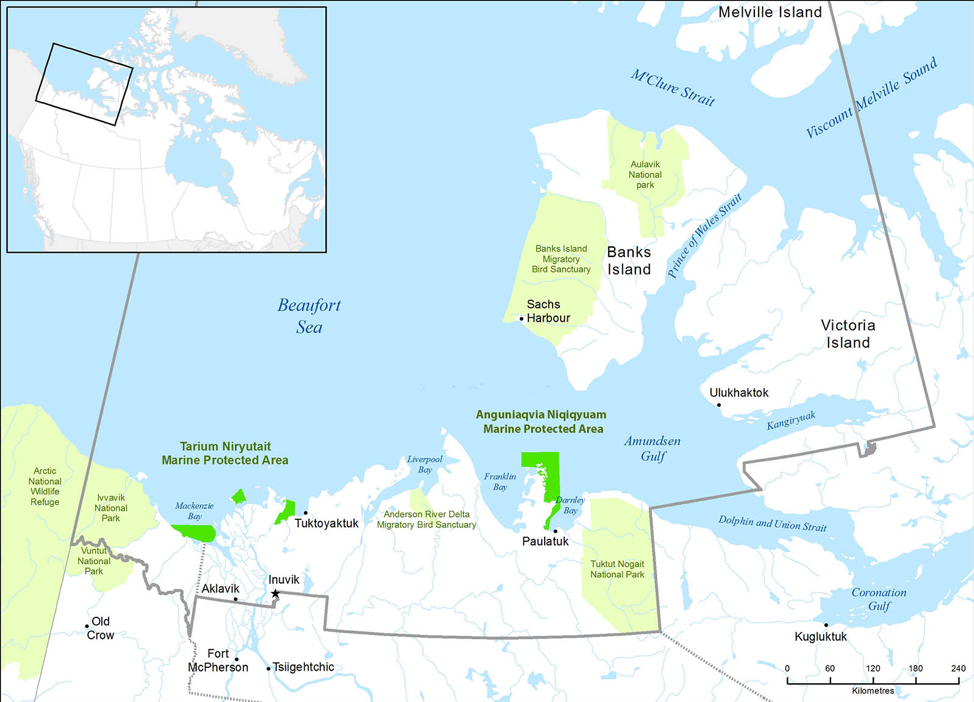

Protected areas within the ISR ©Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Safe Havens

Places like Anguniaqvia Niqiqyuam Marine Protected Area (MPA), and Tarium Niryutait MPA (which is along the Yukon North Slope) provide a high level of environmental protection in regards to industrial activities like oil and gas exploration, mining, dumping, and bottom trawling. But not all of the Beaufort Sea in the ISR has the same level of protection. So this environmental work by folks like Stephen, and everyone involved in environmental management partnerships, will aid in the conservation and resilience of our Arctic home.

Our Science Chats series was created and developed by Kayla Nanmak Arey. She shares a little about herself below:

Nanmak is a name I share with my granny Jean Arey (my great grandmother). My nanak Nellie (grandmother), and my mom Carol say my granny was stubborn, and so was I. Inuvialuit names are passed down from generation to generation, and I am proud to have the name Nanmak. Translated, nanmak means to backpack. Specifically, for a working Inuit dog to carry things in, a nanmak.